Your basket is currently empty!

Category: Brain Vomit

Romancing the AI – Using Neural Networks as part of the creative process

I’m not just an artistic genius you know. I have a day job (well, not at the moment, but let’s pretend) that involves me using clever coding algorithms to tease information out of voluminous and/or complex data sets. It’s both challenging and satisfying and I’m very good at it. It’s also not so different from…

Manga Mannequin Considering Jumping Into the Abyss

Here is a picture of my Manga Mannequin stood staring into the abyss. He seems fearful, hesitant, afraid even. He also has no face to tell us this with. No voice and no story. These Manga Mannequins do suggest a story, or perhaps a character, or element of culture, or something like that. There is strength…

Finished

It won’t find it hard to believe that I find it difficult to focus when on conference calls. A random floating piece of dust catching a mote of sunlight is enough to draw me a away from the matter in hand. The ceaseless distraction that is the social web is like a black hole sucking…

Violent Random Equilibrium

Mornings are good. Spring is good. Spring mornings are all about change, and I like change. The anti-entropic thrust that brings colour and bustle to outside spaces is merely a part of a conspicuous cycle, but always feels fresh after the dormancy of winter. I walk my dog most mornings in a local park. The…

Lower Your Fidelity

A recent musical binge on Car Seat Headrest has lead me to revisit the various lo-fi bands and albums I love from the 90’s. Both Will Toledo’s style and approach owe a lot to that movement, not least to Guided By Voices, but also Pavement, Sebadoh, Sonic Youth and various others to varying degree. Despite…

Pay to Win

I find myself increasingly concerned for the plight of the younger generations. The older generations, who supposedly should be benefactors, mentors, and protectors of their kids’ and grandkids’ futures are repeatedly selling out their futures in favour of short term self interest, base prejudice and ego. While they frown on the kids as video games…

I do not like this

Here’s a painting I made that I do not like. It is, of course, of me, but I only ever meant to use myself as a model. I tried to make it not look like me, but I failed repeatedly and gave up. Perhaps there’s something to be read into that. Pretty much as soon…

I don’t write good?

I don’t. To do so would require the summation of a degree of attention to detail and figurative sense that I lack. I’m as bad at grammar as I am at subtle, emotive symbolism. I’m not saying i don’t recognise the existence of these things, and attempt to diligently apply them, I just lack the…

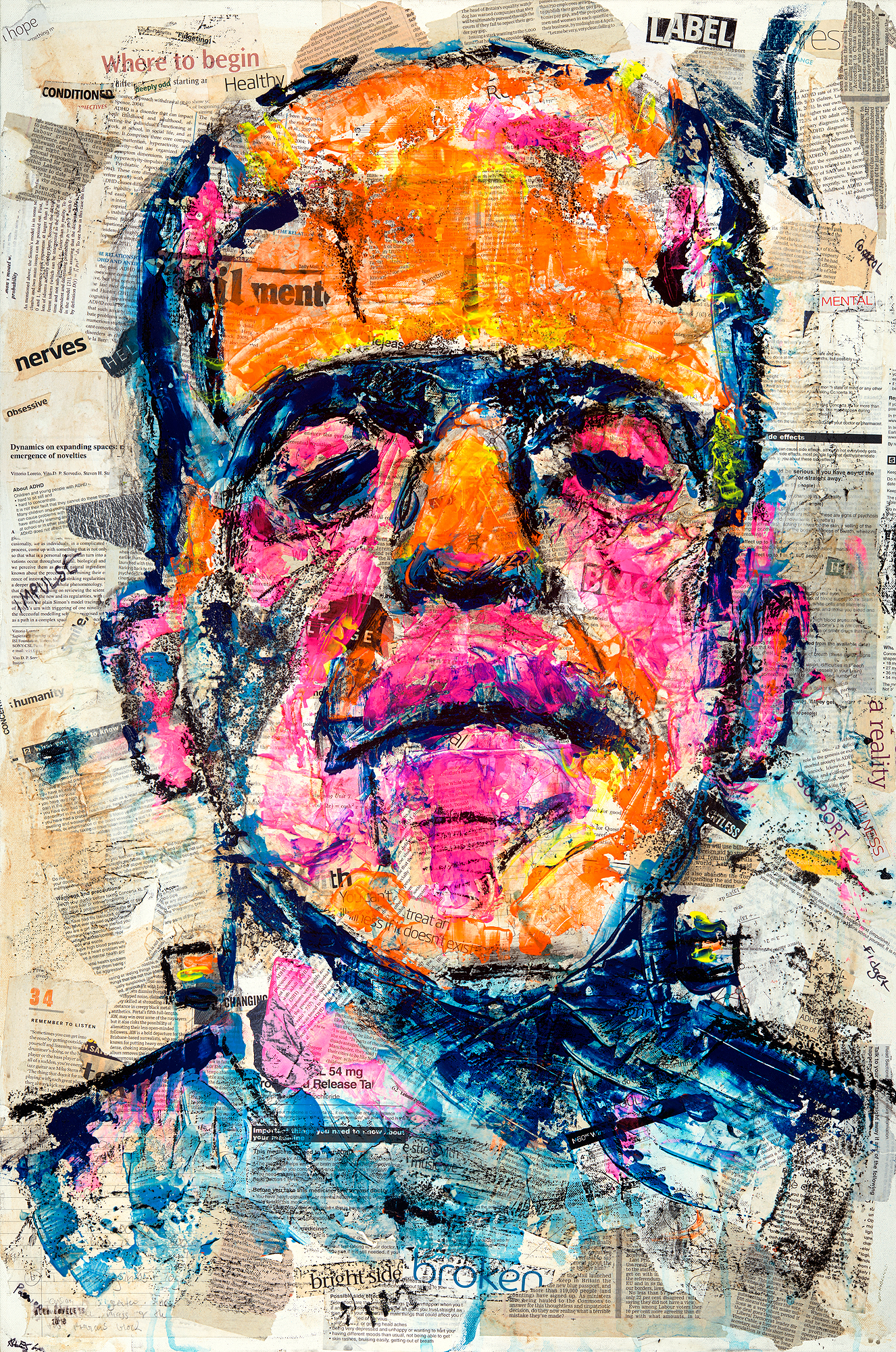

Self Portrait – Light and Dark

This self portrait was submitted to and rejected by Sky Arts Portrait Artist of the Year. I’m sort of glad it didn’t make the cut, as being subjected to an intense four hours of painting surrounded by onlookers and TV cameras would, I think, be a little much for my already hyperactive brain. I accompanied…

Neck Ache

The kids look down at their iPads. The loose style of this painting only emerges as I created it.

A rambling and indulgent treatise on the nature of art and the confusing and terrifying act of creation

I’ve always felt compelled to create things. The idea of creating and presenting a thing, physical or virtual, always felt like some sort of magic – the evocation of something from nothing, the act of transmogrifying and combining one or more things to instantiate something else. I’ve never been particularly picky about my materials, or…