Your basket is currently empty!

Category: ADHD

Romancing the AI – Using Neural Networks as part of the creative process

I’m not just an artistic genius you know. I have a day job (well, not at the moment, but let’s pretend) that involves me using clever coding algorithms to tease information out of voluminous and/or complex data sets. It’s both challenging and satisfying and I’m very good at it. It’s also not so different from…

My studio today and what to do when you’re too close to the edge…

Here’s what my studio looks like today: It’s always a bit of a mess, and since I’m ramping up for an exhibition, it’s particularly chaotic. You’ll note my “washing line” along the back wall. This is actually a washing line chord, but I don’t tend to use it for drying paintings, or clothes for that…

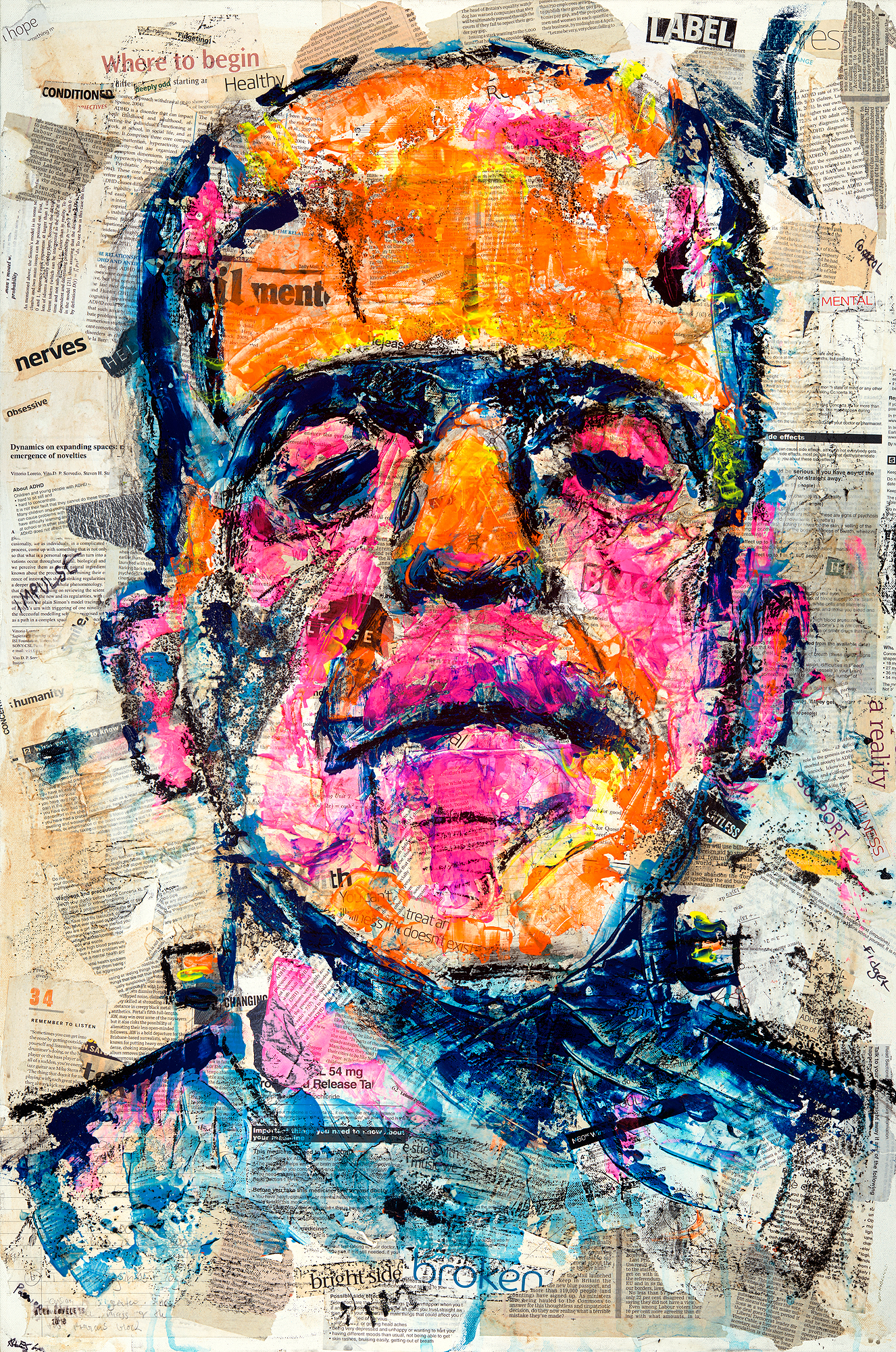

What Makes Us Stronger

“What the hell are we supposed to do now?!” I asked, panicked and confused. A genuine question – what should a hiker do when posed with such a predicament? Having no experience, I genuinely didn’t know. The worried glances of my friends did nothing to calm me. They knew this was bad. “Get the…

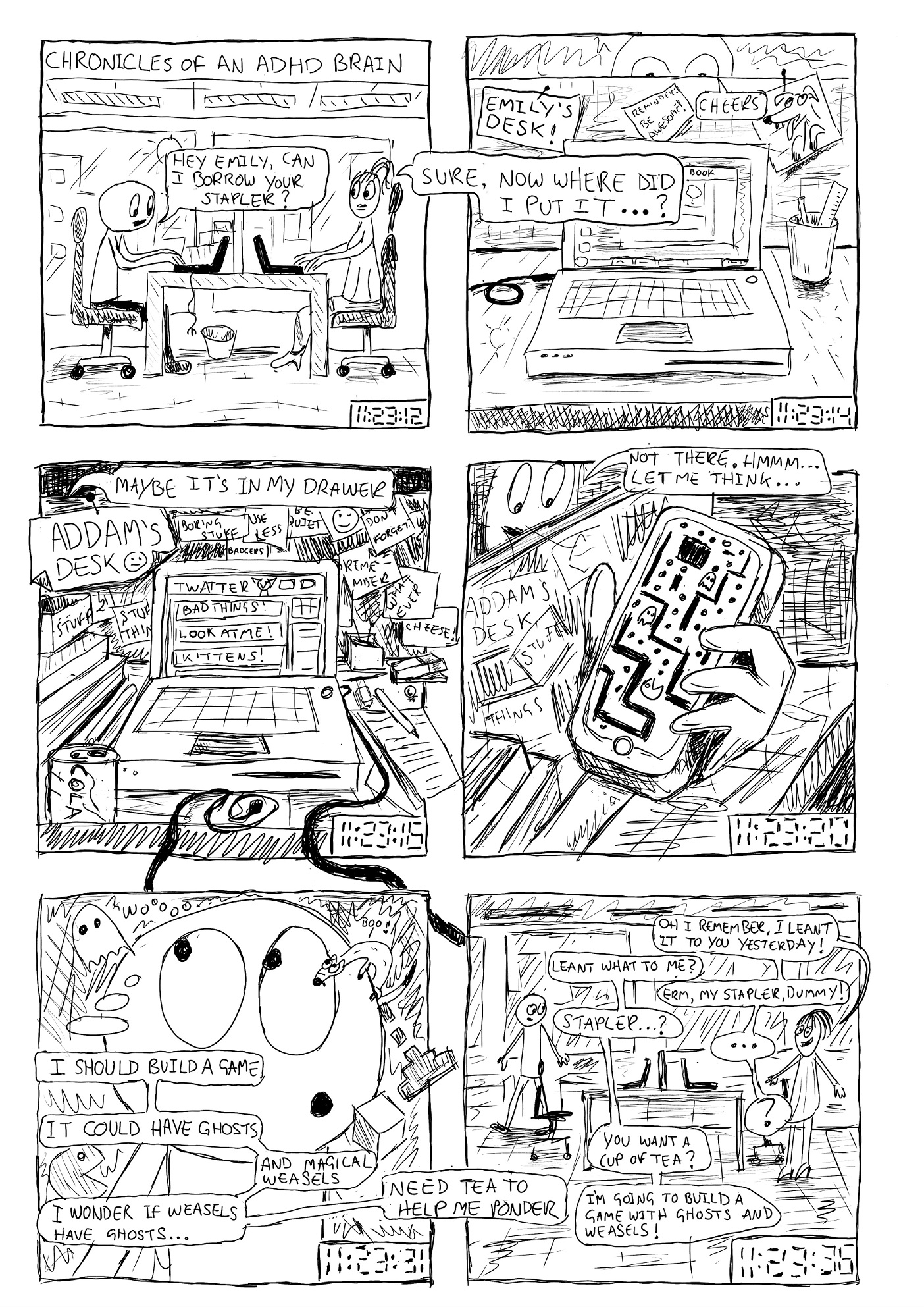

What is it like?

I’ve heard the question posed from time to time “what does it feel like to have ADHD?”. No one has ever, to my memory, asserted this enquiry in my direction, but to be fair, anyone vaguely acquainted with me would know that asking that sort of question would result in too many minutes of their…

I don’t write good?

I don’t. To do so would require the summation of a degree of attention to detail and figurative sense that I lack. I’m as bad at grammar as I am at subtle, emotive symbolism. I’m not saying i don’t recognise the existence of these things, and attempt to diligently apply them, I just lack the…

A rambling and indulgent treatise on the nature of art and the confusing and terrifying act of creation

I’ve always felt compelled to create things. The idea of creating and presenting a thing, physical or virtual, always felt like some sort of magic – the evocation of something from nothing, the act of transmogrifying and combining one or more things to instantiate something else. I’ve never been particularly picky about my materials, or…

Where I End and ADHD Begins

There’s a gap in between There’s a gap where we meet Where I end and you begin And I’m sorry for us The dinosaurs roam the earth The sky turns green Where I end and you begin Where I End and You Begin – Radiohead The ADHD brain goes where it pleases. I have very…

Do Small Things

You have an aunt, or a sibling, or a bezzie don’t you, who you love to pieces but is basically an anal douchebag? You know, the one that, when they walk into your house, tries to conceal palpable distaste at the general disorder and disarray. Like they’re suppressing the mental gag-reflex. You kinda don’t want them to…