Your basket is currently empty!

Month: April 2018

Violent Random Equilibrium

Mornings are good. Spring is good. Spring mornings are all about change, and I like change. The anti-entropic thrust that brings colour and bustle to outside spaces is merely a part of a conspicuous cycle, but always feels fresh after the dormancy of winter. I walk my dog most mornings in a local park. The…

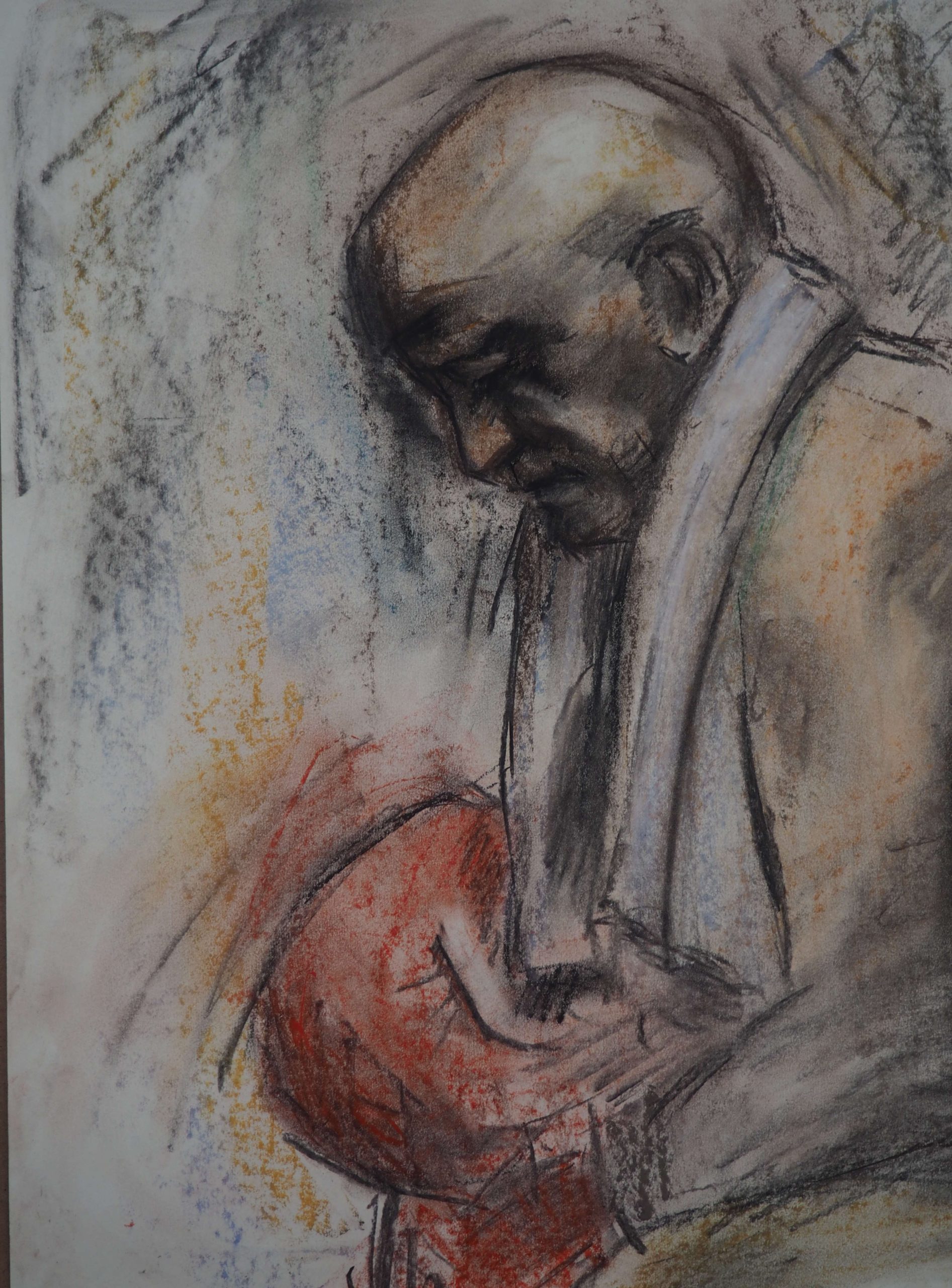

The Boxer

This nice man came to a life drawing session and dressed as a boxer. I don’t know how many pensioners continue to box, so in that sense, the concept is a little incongruous. I suppose this old fighter has adorned his kit for one last time, perhaps to relive former glories and feel some of…

What is it like?

I’ve heard the question posed from time to time “what does it feel like to have ADHD?”. No one has ever, to my memory, asserted this enquiry in my direction, but to be fair, anyone vaguely acquainted with me would know that asking that sort of question would result in too many minutes of their…

Lower Your Fidelity

A recent musical binge on Car Seat Headrest has lead me to revisit the various lo-fi bands and albums I love from the 90’s. Both Will Toledo’s style and approach owe a lot to that movement, not least to Guided By Voices, but also Pavement, Sebadoh, Sonic Youth and various others to varying degree. Despite…

Pay to Win

I find myself increasingly concerned for the plight of the younger generations. The older generations, who supposedly should be benefactors, mentors, and protectors of their kids’ and grandkids’ futures are repeatedly selling out their futures in favour of short term self interest, base prejudice and ego. While they frown on the kids as video games…

I do not like this

Here’s a painting I made that I do not like. It is, of course, of me, but I only ever meant to use myself as a model. I tried to make it not look like me, but I failed repeatedly and gave up. Perhaps there’s something to be read into that. Pretty much as soon…

I don’t write good?

I don’t. To do so would require the summation of a degree of attention to detail and figurative sense that I lack. I’m as bad at grammar as I am at subtle, emotive symbolism. I’m not saying i don’t recognise the existence of these things, and attempt to diligently apply them, I just lack the…

Self Portrait – Light and Dark

This self portrait was submitted to and rejected by Sky Arts Portrait Artist of the Year. I’m sort of glad it didn’t make the cut, as being subjected to an intense four hours of painting surrounded by onlookers and TV cameras would, I think, be a little much for my already hyperactive brain. I accompanied…

Neck Ache

The kids look down at their iPads. The loose style of this painting only emerges as I created it.

A rambling and indulgent treatise on the nature of art and the confusing and terrifying act of creation

I’ve always felt compelled to create things. The idea of creating and presenting a thing, physical or virtual, always felt like some sort of magic – the evocation of something from nothing, the act of transmogrifying and combining one or more things to instantiate something else. I’ve never been particularly picky about my materials, or…